I am poet and not a math person. That’s not to say it’s an inherent flaw with all poets. Most people in general are better at numbers than I am, which I guess is one of the reasons I find them so intriguing. As a concept, complex math exists so far outside my realm of understanding that I can only gaze upon it in awe and remain thankful there are people who can conceive of such wonders.

Poets often have to consider numbers one way or another when addressing form. There’s the 14-line sonnet, the 10 syllables in a line of iambic pentameter, or actual Equation Poetry that invites mathematical symbols and formulas into conversation with a poet’s words. The musicality of phrasing, rhyming structures, meter – math is an essential component of formal poetry. And like all restrictions, creates both structural limits and creative opportunity.

One of the most exciting forms of mathematic poetry are Fibonacci poems. These poems take their structure directly from the Fibonacci Sequence – a numerical series where each new number is the sum of the two numbers that precede it, for example:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89…

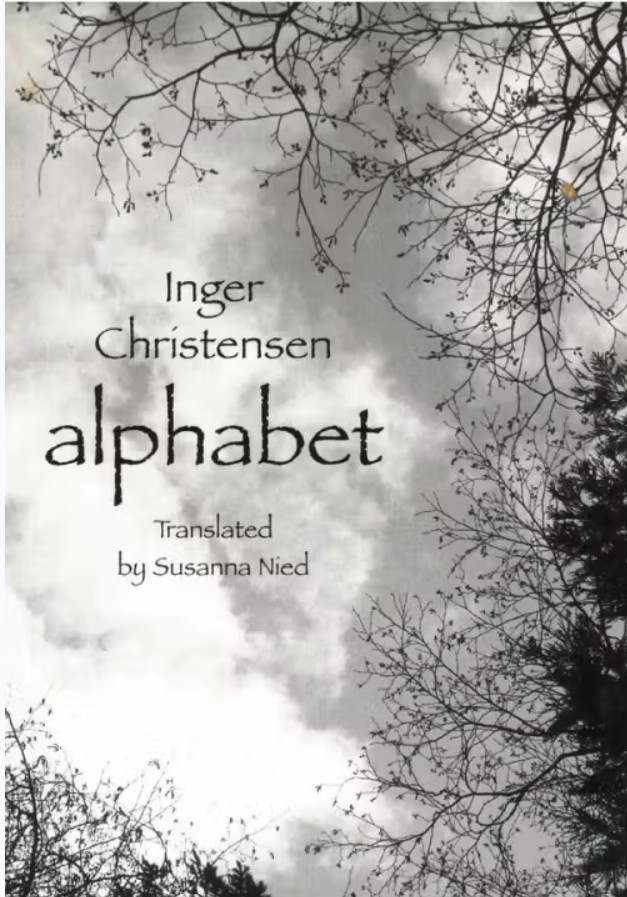

My all-time favorite Fibonacci poem is the famous book “alphabet” by Inger Christensen (translated from Danish by Susanna Nied). It’s a beautifully conceived book-length poem that is both Abecedarian (each line begins with the next letter of the alphabet in sequential order – A, B, C, D, etc.), AND written in 14 sections with each section’s line length dictated by the corresponding number from the Fibonacci sequence. For example: Section 1 of the poem, “A”, has only one line, while the last section of the poem, “N”, has a total of 610 lines.

The poem builds organically, starting with the simple image of an apricot tree – “apricot trees exist, apricot trees exist.” The first few sections of the poem embrace this cadence of repetition and alliteration, naming even more everyday things that exist from blackberries and citrus trees to hydrogen. As each section doubles in line length from the one before it, the poem takes on a natural tension, growing grander in scope both physically and thematically. Suddenly along with ‘early fall’ and ‘elk’, we start to see more abstract ideas like ‘afterthought’ and ‘memory’s light’. These ethereal observations take a more sinister turn by section 7 where “guns and wailing women, full as greedy owls exist…”.

The poem continues to build a world that erupts out of itself, weaving the reader through a complex and mesmerizing tapestry of natural elements and the complexities of the human experience – love, fear, war, death, destruction. And we as the readers are not removed from the equation. We are part of the things that exist and act as a witness to what exists – the beauty and the horror alike.

It’s a wildly successful example of a mathematical form not only supporting the poem visually and musically but reinforcing the very structure of the narrative. The stakes get higher as the lines get longer. The ideas go from granular to metaphysical, starting from that simple image of the apricot tree. It’s complex without being inaccessible and a joy to revisit – even as the darker themes spread their fingers throughout the verse.

My Take on a Fibonacci Poem

When I first read alphabet in the early 2000s, I was inspired to write my own silly version of a Fibonacci Poem by focusing on another anachronistic device – the answering machine. A very long time ago I had an apartment in Oakland with my boyfriend (now husband) Kaleb and our friend Aaron. It had a landline and an answering machine.

Shortly after moving in, we started getting messages for a guy named Jeff, and those messages told the story of a messy breakup between Jeff and Linda. These people were looking for answers they were never going to get – at least not from us. They also never seemed to call while anyone was home. The three of us didn’t know how else to handle the situation, so we changed our answering machine’s outgoing message to break the bad news to all the Jeff and Linda fans. That message inspired the following poem:

The Problem of Answering Machines

(a Fibonacci poem and imperfect response)

…

no,

we

are not

here right now

to accept your call,

but appreciate your attempt

at communication, well aware that this may not

be enough time to record your intentions, but by reducing our connection to

your name, number, and brief outlining of your purpose for contact, citing specific examples of why this conversation may at all

prove pertinent to our overall wellbeing will be useful in deciding whether or not to return said call in any timely fashion as it relates to what time if any we have in the future to commit—

<beep>

Jeff

and

Linda

do not live

at this machine, they

have told us to say that they will

not be returning your call; they have no new number

and no, he does not love her anymore.

– Allison Goldstein, 2005

The first section of the poem mimics an overly long outgoing answering machine message and follows the Fibonacci Sequence with 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55 syllables-per-line.

The poem then resets at the <beep>. The ‘response’ section after the beep also follows the Fibonacci Sequence until the very last line, which doesn’t fulfill the syllable quota and is therefore imperfect (as the title states) to mirror that message that the couple has broken up/disconnected.

Let this be a lesson that it’s fun to play with form – even if you come up with a perfectly imperfect math poem about a technology that hasn’t properly existed in 20 years. Happy writing!